Life is a Never Ending

There is a region on Earth that has not received precipitation in two million years.

The Dry Valleys of Antarctica are shielded from the ocean by high mountains that block seaward-flowing glaciers and encourage 200-mile-per-hour gravity winds whose temperature-driven gusts heat as they descend violently through the atmosphere, evaporating all humidity in their path.

This strange region and the extreme landscape it produces are studied closely by scientists to better understand extraterrestrial conditions and to imagine potential futures on Earth under the increasingly volatile threat of climate change.

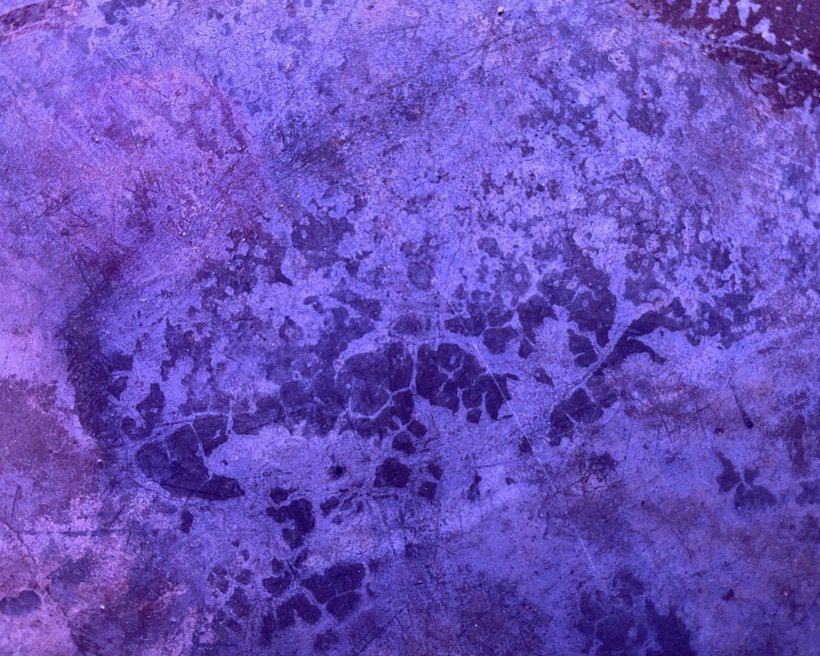

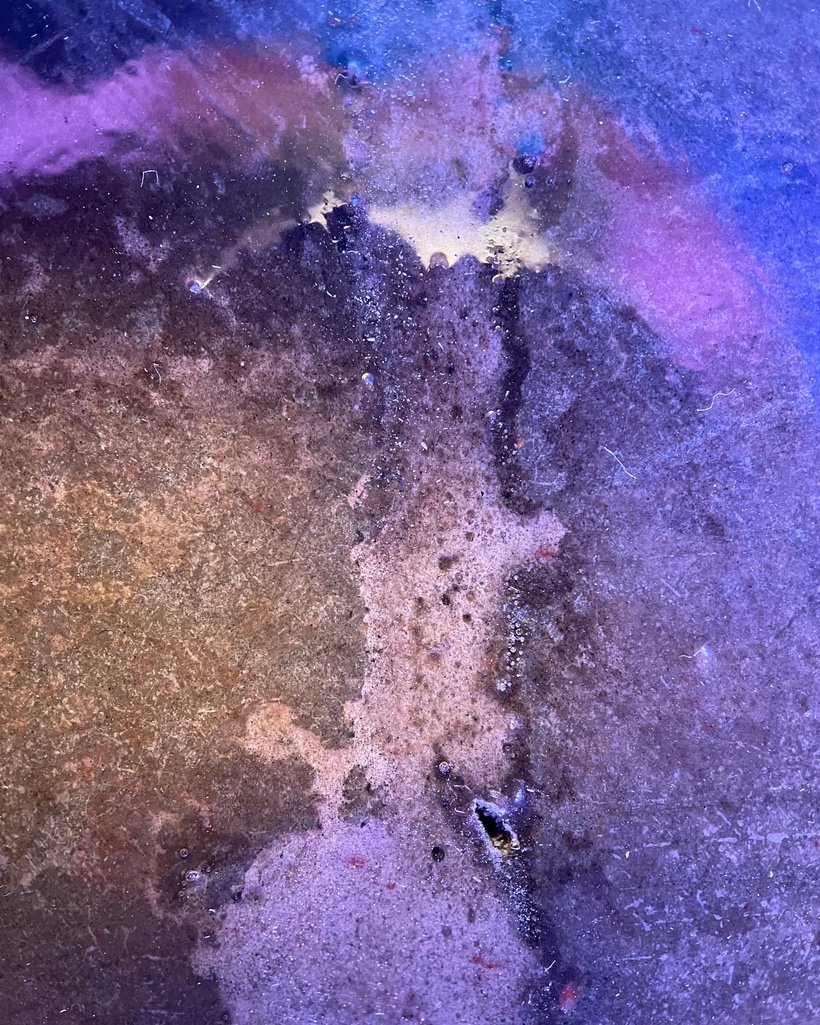

In February 2022, Venezuelan-American artist Rafael E. Vera (b. 1977) inhabited a gallery at the Tarble Arts Center as his workspace, examining the floor in great detail and capturing images using a macro lens attached to his cell phone’s camera, a set of studio lights, and his own body.

The artist meticulously crafted each take by changing the color temperature of the lights and altering their cast using his hands, transforming photographs of a concrete floor into images that recall underwater vistas, galactic voyages, extraterrestrial landscapes, and microscopic slides.

The photographs’ compositions are reminiscent of the black-and-white images that the American artist Rose-Lynn Fisher (b. 1955) took of evaporated tears using a digital microscopy camera attached to a standard optical light microscope. In 2008, during a period of her life that was marked by grief, the artist began collecting and photographing her own tears in a somewhat merciless cataloguing of personal discomfort and pain. The resulting images suggest topographies and landscapes, revealing the varied structures of different kinds of tears. Basal tears (those that protect our eyes from dryness), irritant tears (those that are shed when we slice onions or get dust in our eyes), and psychogenic tears (those that express extreme emotion) consist of different levels of water, minerals, proteins, and hormones, producing different kinds of patterns when viewed through a microscope and captured as images.

Crying has a proven aesthetic quality. Research conducted by psychologists at the University of Pennsylvania examined human enjoyment of initially negative experiences that the body interprets as threatening—eating extraordinarily spicy peppers, for example. The body’s eventual realization that it’s been fooled and that there’s no present danger leads to feelings of pleasure. This process is defined as a kind of hedonic reversal called “benign masochism,” and the study found that people experience greater pleasure in the negative experience of sadness than they do in the negative experiences of physical pain or fear. This kind of harsh pleasure in sadness and crying was most often engaged by experiencing works of art.

Vera described his endeavor to create this work as a “love letter to the floor.”

In her poem “Making Love to Concrete,” Audre Lorde gifts instructions that floor-lovers may want to factor into their exploits:

You cannot make love to concrete

if you care about being

non-essential wrong or worn thin

if you fear ever becoming

diamonds or lard

you cannot make love to concrete

if you cannot pretend

concrete needs your loving

Concrete—the second most-used material on Earth—is certainly not new to being exploited by artists and poets for structure as both a physical and a conceptual device.

Established in Europe in the 1930s, Concretism was an art movement rooted in geometric abstraction and a belief in the power of rationalism to achieve human progress. Concrete artists differentiated themselves from other abstractionist groups by dictating that their art must be wholly nonreferential. According to their strict manifesto, form must be conceived in the artist’s mind rather than borrowed from forms found in nature. The style spread outside of Europe in the 1950s when Latin American artists craved methods of expression that were more elusive than figuration, which could be co-opted by oppressive governments who used artists’ work for propagandist agendas.

A Neo-Concrete movement emerged in Brazil in 1959 when existing Concretist groups began to critique the brutally rational and colonist nature of the European-born movement. Recognizing the limits of rationalism and supposed objectivity, the Neo-Concretists embraced a more phenomenological approach to art-making that took into account an individual’s experience as an embodied entity in the world.

One such artist, Lygia Pape (1927–2004), is perhaps best known for her interactive artwork Divisor (Dividor), which was originally presented on the streets of Rio de Janeiro in 1968. This work relies on an enormous expanse of white fabric, which is punctuated by many holes and activated by a group of participants that “wear” the fabric by penetrating the holes with their heads as though the holes were collars. Each participant’s head is visible above the sprawling plane of the fabric while their bodies move collectively below the surface and out of sight. This topography of bodies captured together as one undulating wave collapsed the boundaries between art and everyday life, and it is often cited as a precursor to the conceptual art practices that arose in the late twentieth century.

Conceptual art prioritizes the idea inspiring a work of art over the finished image or object, and conceptual artists use whatever material or form best conveys that idea. German artist Wolf Vostell (1932–1998), a founding member of the concept-driven Fluxus movement and one of the earliest performance, video, and installation artists, used concrete as a material in his work beginning in the early 1960s. He used still-wet concrete as a painting medium in two-dimensional works, and also created sculptures by freezing common mechanical products such as cars and televisions into static blocks by covering them in concrete that was left to cure from fluid to solid form.

The artist often displayed these sculptures in settings that put them in close proximity to other fully operational consumer products to create a juxtaposition between realities—the familiar comingling with the unfamiliar, conventional ideas deconstructed by the disruption of such confounding art objects.

The word concrete itself has many meanings—and collectively they demand the existence of material form rather than abstract idea. To be concrete is to be solid, specific, definite. To be set. To cure.

Vostell’s work depends on the physical nature of concrete—one of impenetrability—while simultaneously suggesting that the violence of concrete’s permanence could function as a potential remedy for inflexibility.

Concrete poetry as a genre describes an approach to the page in which the visuality of letterforms and typography adds to or perhaps even dominates the meaning of words. But any kind of poetry, regardless of style, constructs meaning by relying on arrangement as a tactic.

To make love to concrete

you need an indelible feather

the lesson of a wooden beam

propped up on barrels

across a mined terrain

The University of Pennsylvania researchers note that the mind-over-body process of benign masochism can be conceptualized as a kind of mastery of cruelty. Pleasure is found in mastering the ability to distance oneself from the initial negative sensation.

Photographs innately arrange a temporal distance. Capturing an image in the photographic process uses light to freeze a moment in time, delivering it from the past into a perpetual present. Inversely, this imposed gesture of image-making forces the subject of the photograph’s present into an immediate past tense. Linear concepts of time collapse into a more fluid movement.

Inland arctic water flows into Dry Valley watersheds where it evaporates, leaving a high concentration of minerals.

As a material, concrete is an aggregate of fine sand, coarse rocky material, and loose stones that has been bonded with a watery mineral cement. Water is the only substance in the world used more often than concrete.

In the Dry Valley, fishless meltwater streams flow away from the ocean and into lakes with salinities more than ten times that of seawater. The only living creatures in this region are endolithic bacteria who are trapped inside rocks and rely on the thermal buffering, mineral traces, and interior moisture that this eternal containment provides.

Vera’s engagement with concrete as material and architecture as form is longstanding, and the use of saturated color and overall composition is predicated by his early work as a painter. His sensitivities to how architecture and space hold the human interactions of teaching, learning, collaboration, and conversation have been present throughout his life as an artist. These sensitivities are evidenced in his use of abstraction and negative space in earlier works that include a meticulously rendered drawing of a concrete architectural foundation, a sculptural stack of cinder blocks wrapped lovingly in silk organza, and a cast concrete slab resting on a pillow that was custom-made for its weight.

between forgiving too easily

and never giving at all.

To be held—whether within the architectures of a room or a soft pillow or a hand or a heart—can be a curing measure.

Frozen and seemingly dead salt-loving microbes—whose bodies had been suspended in arctic ice 2,800 years ago—were recently thawed and reanimated by scientists in a lab. These formerly captive organisms went on to grow and thrive on their own without any additional contact or containment.

To hold or hold onto something or someone—whether within the geographies of a tundra or a memory or a body of water or an image—requires a closeness that can be as much an act of cruelty as it is an act of care.

Installation view of two early videos by pioneering video and installation artist Pipilotti Rist

Video, Visibility, Voice

(read more)

In the middle of the twentieth century, video emerged as an electronic medium that allowed for new ways to record, copy, play back, and display the moving image. The technology was originally intended to capture and replay live events for television, but as consumer video recording and playback equipment became affordable in the early 1970s, video cassette recorder (VCR) decks and tapes became an increasingly popular means to record and revisit everyday content of all kinds. Preceding the proliferation of camera-handed parents and backup-batteried tourists whose lives soon became the stuff of home movies in the 1980s and ’90s, artists were attracted to this technology’s potential to forge new expressive methods. Creative curiosity led many avant-garde artists of the 1960s and ’70s to explore video as an artistic medium.

Intallation view of a two-channel video installation by Shirin Neshat

These artists quickly recognized the opportunity to create inexpensive production and distribution systems that could not only evade rigid art markets but also thwart the ingrained, often dusty ideals that ruled more traditional media. The liberating potential of an infinitely reproducible medium without the weighted history of gendered expectations like painting and sculpture was especially attractive to second-wave feminists. Artists like Martha Rosler and Joan Jonas combined video with performance to explore time, the body, and the phenomenon of being an observable object—in other words, the experience of being watched.

Scholar Lauren Fournier invites us to consider autotheory as an interdisciplinary feminist aesthetic mode with which to explore the history of creative practices and systems of critique. In tracing the lineage of contemporary autotheory, Fournier connects it to the history of feminist theory and in particular to feminist performance, video, body, and conceptual art practices as well as the intersectional feminist writing by women of color like Audre Lorde, who claimed, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” We see this autotheoretical impulse within the works featured throughout the exhibition Force Majeure, and it is tangible in the writings of Cole Lu and Catalina Ouyang that are published in the catalogue that documents the exhibition. Each artist has either filmed her own body moving through landscapes, recorded their own confessions, or positioned women’s voices in opposition to men’s bodies in order to recount and understand their own observations, performances, agreements, failures, traumas, lamentations, and escapes.

Force Majeure, then, is the voice of a speaking subject, a clause, an exhibition, and a book. In each way it accounts for contingency and allows space to evade the imposed obligations of institutionalized understandings. It is the absence of an organic reality in favor of multiple projections, an absence of necessity as an invitation to imagine. It is the experience of being so without having to be so, of being sewn without having to be cut, of possibility without certainty—extending what goes unseen to becoming what is unforeseen.

LILLY MCELROY

Historically speaking the sun is a god, luminous source of all earthly energy, creator of life, untouchably distant. This massive ball of burning plasma’s reach is seemingly boundless, looming over the land, emitting rays that permeate every day, and reflecting into all but the darkest nights. The sun provides its subjects with warmth and life while it also threatens to burn their skin, make them blind, and eventually kill them.

This inherently uneven power dynamic is ever-present and overwhelmingly embedded into one’s understanding of existence in a heliocentric world, and the desire to possess such force is inherent to the practice of photography—a process of capturing light. In this exhibition, a year’s worth of suns—365 photographs of the setting sun in the landscape—are collected, stacked into a monolith, and methodically altered by the artist’s hand. Day by day, McElroy has sanded through the stack of images toward the source of light—a gesture that is small, intimate and tender, yet ultimately removes the sun as the subject and replaces it with a growing void. The act of erasure is accomplished through the insertion of a female form— represented in this body of work by the agency of the artist’s body as well as a chasm that grows more and more vulvic after each hour of sanding, and in other works which enact the fold as a tool for obliteration. When the appearance of the sun is permitted by the maker of these images, it is heavily controlled through illusion, at times bridled by the artist’s own hands.

McElroy’s explorations present a cinematic approach—making film edits with physical pleats, moving backward in time through the removal of matter, and creating theatrical sets that recall megalithic light-keeping calendars. While duration is certainly a measure of time, it also often functions as an appraisal of both labor and love.

May god thy gold refine

Garry Noland makes himself known as a jolly scrimshander of trash, incising psychedelic patterns, maps, and portals into polystyrene, pieces of cardboard, and stacks of old magazines. He weaves textiles and gilts objects gold with polyetheyne tape, creates mosaics with shining tesserae marbles, and confidently posits that monuments can be dredged from polluted urban lakes. He wears a vintage mohair cardigan and is quick with a bad/dad joke. He has a rigorous and sacred studio practice, to which he shows up daily and works diligently, letting the materials he sources from dumpsters, sidewalks, and his studio floor guide his process with an almost religious faith in their ability to reveal underlying truths.

Across his varied artistic practice, Noland cites the abutments between boundaries—whether formal or conceptual, historical or contemporary, playful or serious, grand or mundane—as a reflection of human interaction with art and with each other. The phrase “living in the moment” is as banal and easily dismissed as Noland’s raw materials, and it functions to describe his practice and the resulting presence of the objects and images he creates. With borders and frames that are often fugitive and contingent properties that literally and figuratively lean into one another, these works are charismatic instigators that implore viewers to engage actively with the present physical, social, political, and emotional spaces we inhabit.

precipitating time

There is a palpable quality of stillness in the thirty minutes before rainfall: a suspension of atmospheric breath presaging an impending tearful confession, the calm before the storm. Eventually, this stillness is interrupted by slow winds rolling across a landscape, bringing with them the scent we’ve come to recognize as something soon torrential. The fresh, crisp smell is the aroma of ozone, a word that derives from the ancient Greek meaning, “to smell.” The pale blue gas is carried by downdrafts from the stratosphere to the troposphere where it reaches our noses. Unlike our senses of vision, hearing, touch, or taste, smell is not relayed through our brain’s thalamus—instead it travels through the olfactory bulb, which is directly connected to the amygdala and hippocampus. These are the areas of our brain that also process memory and emotion, and this biological pathway might explain why scent so easily triggers such intense and sometimes unexpected episodes of nostalgia.

The weight of footsteps on a damp forest floor agitates soil underfoot, and the wet, musty aroma that accompanies this disturbance immediately places one’s sensibilities in the natural world. Geosmin, a metabolic byproduct of bacteria, is the substance emitting this smell, and despite the scent’s association with growth, life, and generation, it can only be released once the bacteria have died. During droughts, plants exude an oil that is absorbed by the clay in rock and soils. This oil is thought to slow the germination of seeds, improving their potential to successfully grow when rainfall is more abundant. Once it does rain, water releases the oil into the air along with geosmin, and the combined scent of these compounds creates petrichor, or put simply, the scent of rain.

A group of school children on a field trip from Kansas City Public Schools visits Leeah Joo’s Project Wall.

leeah joo

Leeah Joo is a Korean-American artist who explores cross-cultural experiences by combining Eastern and Western painting traditions to examine the act of looking. Her compositions often depict what is covered and/or what remains hidden. Presenting a vista of silk wrapped mountains and valleys, Sexybeast (2017) sets the stage for Korean folklore and history to unravel before a contemporary American experience. The drapery in this work is inspired by one of Kansas City’s most treasured American masterpieces Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception by Raphaelle Peale:, which hangs in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Peale’s trompe l’oeil painting is the pinnacle of obfuscation both in its overt subject—a reinterpretation of John Barry’s 1772 painting Venus Anadyomene wherein Peale has painted a white sheet strategically hung to hide the nude Venus behind it—as well as in the evidence of an underpainting. During a Peale family exhibition in 1967, an underpainting with striking similarities to a portrait of Peale painted by his own father was discovered. The discovery of this pentimenti has lead historians to believe that Peale copied—and then painted over—his father’s work.

Peeking over the v-fold in Joo’s violet swathed hilltops is a traditional Korean goblin or dokkaebi in place of the Venus. The dokkaebi is a fearsome supernatural beast known for pranks that ultimately prove to be harmless. In this composition, the leering goblin stands in for a different example of patrilineal inheritance: Kim Jung Un, Supreme Leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea). This conflation of a contemporary figure and mythological creature can be read as a painterly incantation or binding spell, wherein the artist marks the megalomaniacal leader as impotent to inflict any lasting harm.

sonya clark

Sonya Clark draws on fiber craft techniques as well as performance to explore the complexity of material culture and stories laden within. The artist learned the value of storytelling from her Trinidadian and Jamaican family, and it was her maternal grandmother—a professional tailor—who first taught her how to sew. This personal history has attuned Clark to the narratives embedded within materials and their potential for telling powerful stories about history, politics, race, and class.

Gele Kente Flag (1995) is an elongated handwoven textile featuring fragmented elements of the American flag interspersed with sections of brightly colored and brilliantly graphic Western African kente cloth. Native to the Akan ethnic group of southern Ghana, kente (derived from the Akan word for “basket”) is one of the most recognizable of African textiles, known for its sumptuous colors and striking geometric motifs. Traditionally, it is woven with silk and cotton threads on a specially-designed loom, resulting in bands of fabric that can then be pieced together to create clothing and other goods. The pan-African colors of the Ghana flag (red, gold, green, and black) are often prominent in the design, though they are interpreted into a range of patterns established through centuries of practice and continually expanded upon by contemporary weavers. In making this work, Clark employed a European loom to create an African weave in which the stars and stripes of the American flag are interspersed with kente designs that convey ideas about prosperity, strength, endurance, advancement, and achievement.

The storytelling potential of Gele Kente Flag can be understood through the interwoven iconography of American and African material cultures and even further through the performative iteration of the project. Clark—who describes the head as “a sacred place, the center where cultural influences are absorbed, siphoned, and retained, and the site where we process the world through the senses,”—invited fifty African-American women to be photographed wearing the kente flag as a gele, or traditional Nigerian head wrap, and, further, invited the women photographed to share their feelings about kente cloth, the flag, and the term “African-American.” Through enacting the cloth in a functional way and giving lived dimension to its hybrid physical structure, Clark imbued the textile with an even more layered composition of hybrid identities and interlaced desires, beliefs, and notions of cultural pride.

State of the World installation view, featuring Allison Smith’s A Hatespun Flag: The Prepper’s Blindspot

Allison Smith

Commissioned by the H&R Block Artspace for this exhibition, Allison Smith’s A Hatespun Flag: The Prepper’s Blindspot (2017) is a large flag composed of hand sewn piecework linen digitally printed with images the artist sourced from Ebay, Etsy, and other consumer websites selling resources that support Viking, American Colonial, Revolutionary War, and Civil War reenactment culture. The items featured in the printed images range from hand-sewn clothing and props to traditional quilt-making calico fabrics and Civil War reproduction sewing kits, the latter two making reference to the making of this work. Mimicking the structure of a quilt, Smith’s flag calls to mind the history of quilting as a gendered communal activity and site for social exchange, but here notions of warmth and mending inherent to needlework are interrupted by a sinister darkness: the homespun has transformed into the “Hatespun” in this flag made for a fictitious paranoid survivalist “Prepper.”

By sourcing images from the Internet, Smith calls attention to a contemporary economy of these goods and lifestyles. The aesthetics of the fundamentalist/survivalist/historical reenactment costumes, objects, and practices—which might easily be mistaken for hipster/artisanal craft/DIY aesthetics—read as authentic and homey, but the extreme devotion to—and ilk of nostalgia manifest in—reenactment culture can be viewed in alignment with the significant rise in conservative nationalist attitudes and agendas seen recently throughout Europe and the United States.

Several of the images in Smith’s flag refer to fire-starting materials: flints, newspaper and herb bundles, red candles bundled like dynamite, and improvised bombs made from Mason jars. These can be read as allegories for paranoia, fear, gaslighting, survivalism, violent protest, and flag burning. But, alternately, these images might illustrate a protest strategy Smith noted in a November 2016 lecture at the Kansas City Art Institute, immediately in the wake of the election that put Donald Trump in office: “Ignite a light, be a catalyst for powerful thought and ideas.”

James Woodfill’s Flag Kit - Dispatch 2

James Woodfill

When James Woodfill was a student at Kansas City Art Institute, he made a living sewing for a local commercial flag company. This particular arrangement informed a twenty-year investigation of functionality, materiality, abstraction, and modes of signaling in both visual art and flags. With a resistance to producing static objects and an objective to “collaborate with the built environment,” Woodfill’s installations and public art projects use light, sound, video, and/or kinetic elements to activate the space of the everyday in the time of human perception.

James Woodfill’s Flag Kit - Dispatch 3

Invited to create a site-responsive installation for this exhibition, Woodfill delivered a portable kit of handmade flags, weights, tethers, and hardware. Flag Kit – Dispatches 2-5 allows for multiple compositions or “dispatches” that can be easily scaled and quickly altered to suit a given environment. Flag Kit began in the artist’s studio as Dispatch 1, has since grown into Dispatch 2, and will continue to transmit messages as Dispatches 3-5, appearing at regular intervals throughout the exhibition. The first configuration is a sharp horizon of flags hanging from the ceiling, stationed at a diagonal to the walls in the alcove it inhabits, revealing itself slowly to a viewer as they enter the gallery space. This creates a surprising encounter that courts both the familiar: we recognize the flag as a form; as well as a sense of uncertainty: what do these strange flags represent? The functional apparatuses and hardware are revealed and in full view; however, the artist’s conceptual aims remain more elusive.

James Woodfill’s Flag Kit - Dispatch 5

Each “dispatch” references systems of flag signaling without ever fully adhering to the parameters of the system. These flags are made of unusual materials and deviate from standard sizes. They may have individual significance, or perhaps they only function in concert, each reliant on its position relative to others in order to convey a larger meaning. While they do appear to relay some kind of free association—one can identify formal relationships, visual rhythm, abbreviated symbols, and even text; the rows of flags never quite materialize into fully-articulated communication. Instead they read as noise or chatter. Woodfill invites his audience to intercept this chatter, examine it, and deduce information from the patterns he presents. Questions proliferate about what each flag implies, if there is a flag code that corresponds to this kit, and whether these dispatches will reveal information about hidden intentions and actions.

While flag signals were invented to solve the problem of communicating over great distances, Woodfill’s flags reward physical proximity. The configuration provides pedestrian space to move in and out of the installation; and tactility, color, transparency, and light summon an intimate investigation. These signals do not aim to breach a spatial distance, instead they endeavor to connect temporal intervals. An established flag vernacular has been reiterated into a present tense that anticipates future communiqués. Will the impending transmission be a memory or a message? And do we expect it to deliver an idea or an event?

Felix Gonzalez Torres’s "Untitled" (Placebo Landscape-for Roni) installed at the Pulitzer Art Foundation in 2016

felix gonzalez torres

A glistening gold carpet of foil-wrapped candies lies directly on the gallery floor in the shape of a rectangle, inhabiting all but the walkable perimeter of the long, lower-level space. The perceived luxury of glistening gold is belied by the humble, remarkably horizontal arrangement and the fact that the material itself is banal, ubiquitous, and hardly untouchable. In fact, a gallery assistant is likely to invite you to not only touch the artwork, but to take a piece of it.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957-1996) is known for employing the evocative potential of minimal forms, and for offering pieces of his work to viewers as a means of dispersal. "Untitled" (Placebo Landscape-for Roni) is the largest of Gonzalez-Torres's "candy spills," a series that consists of replenishable piles of commercially available sweets. These can be installed in various formations determined by the exhibiting institution, and will be altered over time by the audience that consumes the work. The title of this particular work-the last candy spill created before the artist's death due to complications from AIDS—contains references to both a perceived medical cure and his close friendship with fellow artist Roni Horn, whose compressed gold sculpture Gold Field ignited a recognition of their shared sensibilities.

Gonzalez-Torres's allusive title reflects the way that one creates meaning through perception and sensation. The shrinking and swelling topography of gold cellophane-wrapped candies beckons a downward gaze, encouraging the body to take on the posture of reverence, mourning, and supplication. This Eucharistic gesture seems at odds with the the base gratification of tasting some thing sweet. Drawn by the desire to take a candy, a series of actions then unfold that include choosing it, unwrapping it, ingesting it, and discovering its flavor. The body transgresses here by not only touching the artwork, but by sucking it, and by contributing to its gradual disappearance. The work is an invitation to acknowledge action as a symptom not only of desire, expectation, and pleasure, but also of consequence. What does one do with the empty gilt wrapper, after all?

Roman Ondák’s Clockwork installed at the Pulitzer Art Foundation in 2016

Roman OndÁk

A gallery assistant asks each visitor these two questions, writing the information with a black felt pen directly onto the wall. The answers become the last line in a neat sequence of handwritten columns, one for every day of the exhibition, framed by a red mason line anchored by two plumb bobs. Clockwork by Roman Ondak (b. 1966) transforms one of the Pulitzer's galleries into a visual representation of time's passing, wherein visitors become the unit of measurement.

Roman Ondak often creates participatory and immersive artworks that stage interaction between museum staff and visitors in new ways that investigate social codes, rituals, and forms of exchange. In the tradition of art that engages the public as both viewer and performer, Ondak aims to question expectations of the museum-going experience by revising a gallery assistant's role and by playing with the convention of didactic timelines and diagrams. In Ondak's Clockwork, time is measured by people, whose arrival generates the marks intended for both a present and future audience.Time is often measured according to an accumulating past, as seen in geologic maps of sedimentary shifts, and Ondak's version of this model simply reorients accumulation by depicting human presence in a growing vertical stratification. More than just an instrument of horology, the performance also acts as a gauge for other possible records and measurements. One wonders if rainy weather, for example, influenced the length of the column created last Thursday. The work also asks questions of networks and connections among its participants: who, separated by only a minute, came together, and who were simply strangers with corresponding schedules?

Clockwork creates an ever-changing composition that allows viewers to become part of the artwork. The museum's walls assume the role of a guestbook, but they enact a form of benign surveillance as well, reminding visitors that reporting one's presence or "checking in" populates a public ledger of behavior and activity. As a collective display of communication, memory, and place, the performance reveals the relative nature of measurement and asks the viewer to recognize how time influences observation.

ventriculus: residue of subjectivity

Adopting an interdisciplinary approach, this volume explores representations of skin in literature, art, art history, visual media, and medicine and its history. The essays collected here probe the symbolic potential of skin as a shifting sign in various historical and cultural contexts, and also examine the material and organic properties of the body's largest organ. They deal with skin as a sensual organ, as an interface or contact zone, as the visual marker of identity, and as a lieu de memoire in different periods and media. In its material characteristics, skin is regarded as a medium, a canvas, a surface, and an object of both artistic and medical investigations. The contributions investigate representations of skin in sculpture, painting, film, and fictional, as well as non-fictional, texts from the 16th century to the present. The topics addressed here include the problematic representation of racial identity via skin colour in various media; the sensual qualities of the skin, such as smell or taste; the form and function of tattoos as markers of personal, as well as collective, identity; and scars as signifiers of personal pain and collective suffering.

![Radiator[6].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c5e28abce17625eb718b7c/1569225974578-9BS2FXUR298GJI92GN2E/Radiator%5B6%5D.jpg)